Technoference and Toddlers

Written by Theodora Coroliuc. Edited by Abigail O’ Connell and Michelle Downes

What is Technoference?

Have you ever had your conversation with another adult or interaction with a child interrupted by a buzzing phone or something loud or interesting on the TV playing in the background? That is what we call technoference! Technoference is formally defined as interruptions to interpersonal activities resulting from screen technologies (McDaniel & Radesky, 2018).

Did you know:

Technoference involves common devices found in the home, including TVs, smartphones, tablets, laptops, and even smart home devices like the Alexa.

Technoference can occur in everyday activities, including playtime, mealtime, bedtime routines, and even while running errands.

Some Surprising Toddler Technology Stats from around the world:

In a recent Turkish observational study of 32 infants at 8, 10, and 18 months in their home environments, researchers found that background TV was on 25% of the time at 8 months, 21% at 10 months, and 17% at 18 months (Uzundağ et al., 2024).

In a recent U.S. survey, 39% of children under eight live in homes where the TV is on most of the time or always, even when no one is actively watching it (Rideout, 2021).

A recent Indian study found that 73.34% of children aged between 6 months and 4 years use smartphones regularly, and usage was found to increase with age (Shah & Phadke, 2023).

Why do we care about the influence of technoference on toddlers?

For toddlers, everyday moments of connection, especially during play, are thought to be key for building language, social and, cognitive skills (Kelly et al., 2011; Glascoe & Leew, 2010). When technology interrupts these moments, development may be impacted in ways we’re only just beginning to understand.

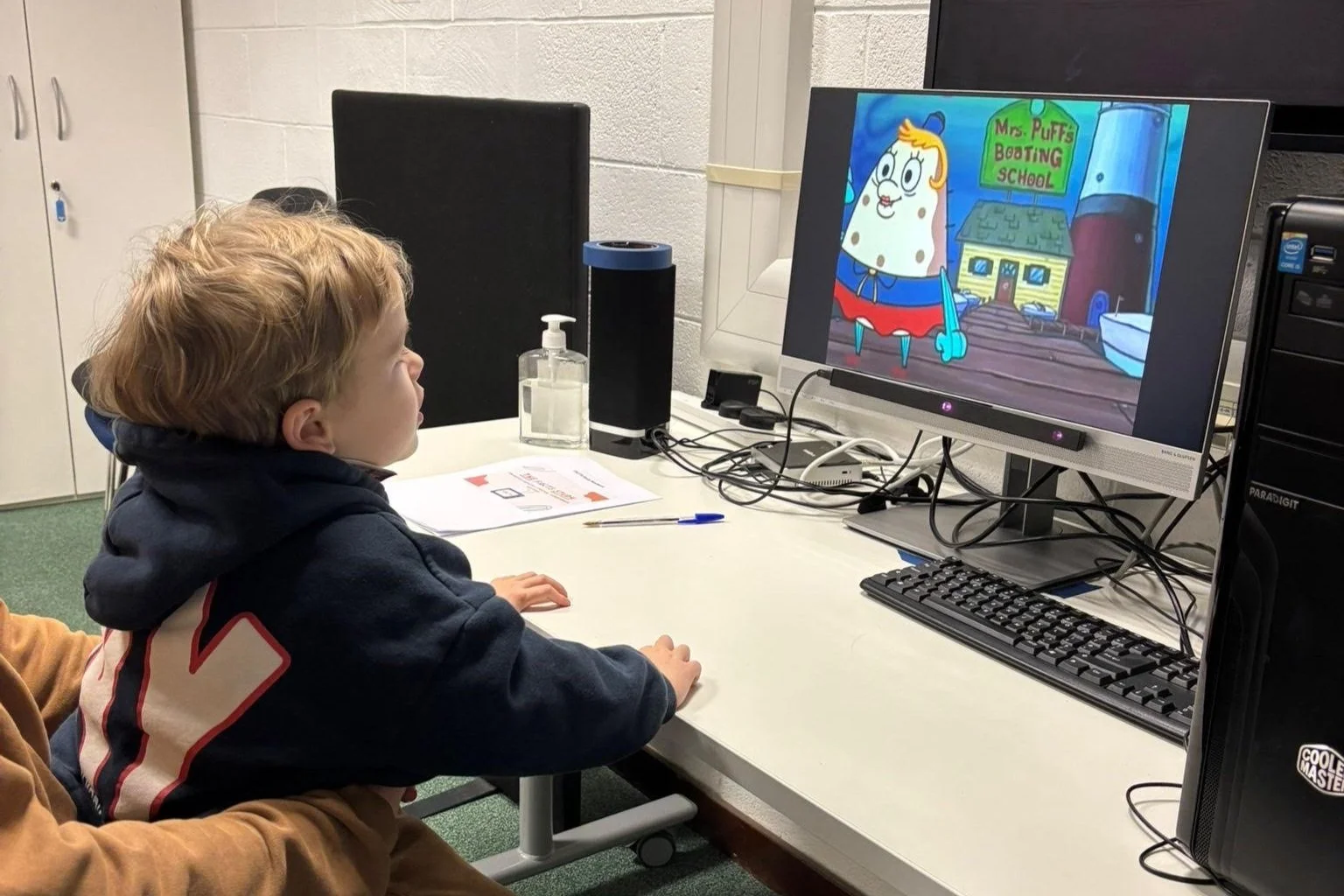

One area we’re particularly interested in at the UCD Babylab is how technoference influences executive functions – the skills that help toddlers plan, regulate, and manage their behaviour (Duncan, 1986; Pennington & Ozonoff, 1996). These critical skills are highly sensitive to environmental influences (Nathanson et al., 2014; Bernier et al., 2012; Zelazo & Carlson, 2012). At the UCD Babylab, we are investigating how technology, specifically technoference, fits into this puzzle.

What’s Next

We are excited to be recruiting for our FACTS Study! This fun research project explores how technoference, fantastical cartoons, sleep, and executive functions interact during toddler development. If you are interested in learning more about the study and have a toddler aged between 18-24 months who wants to take part, we want to hear from you! You can find more information by clicking here.

If you would like to find out if you are eligible to take part in the FACTS study, please click here!

References

Bernier, A., Carlson, S. M., Deschênes, M., & Matte‐Gagné, C. (2012). Social factors in the development of early executive functioning: A closer look at the caregiving environment. Developmental science, 15(1), 12-24.

Bibok, M. B., Carpendale, J. I., & Müller, U. (2009). Parental scaffolding and the development of executive function. New directions for child and adolescent development, 2009(123), 17-34.

Carlson, S. M., & Moses, L. J. (2001). Individual differences in inhibitory control and children's theory of mind. Child development, 72(4), 1032-1053.

Conway, A., & Stifter, C. A. (2012). Longitudinal antecedents of executive function in preschoolers. Child Development, 83(3), 1022-1036.

Duncan, J. (1986). Disorganisation of behaviour after frontal lobe damage. Cognitive neuropsychology, 3(3), 271-290.

Glascoe, F. P., & Leew, S. (2010). Parenting behaviors, perceptions, and psychosocial risk: impacts on young children's development. Pediatrics, 125(2), 313-319.

Hughes, C. H., & Ensor, R. A. (2009). How do families help or hinder the emergence of early executive function?. New directions for child and adolescent development, 2009(123), 35-50.

Kelly, Y., Sacker, A., Del Bono, E., Francesconi, M., & Marmot, M. (2011). What role for the home learning environment and parenting in reducing the socioeconomic gradient in child development? Findings from the Millennium Cohort Study. Archives of disease in childhood, 96(9), 832-837.

McDaniel, B. T., & Radesky, J. S. (2018). Technoference: Parent distraction with technology and associations with child behavior problems. Child development, 89(1), 100-109.

Nathanson, A. I., Aladé, F., Sharp, M. L., Rasmussen, E. E., & Christy, K. (2014). The relation between television exposure and executive function among preschoolers. Developmental psychology, 50(5), 1497.

Pennington, B. F., & Ozonoff, S. (1996). Executive functions and developmental psychopathology. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry, 37(1), 51-87.

Rideout, V. (2021). The Common Sense Census: Media Use by Kids Age Zero to Eight in America, A Common Sense Media Research Study,[United States], 2013, 2017.

Shah, S. A., & Phadke, V. D. (2023). Mobile phone use by young children and parent's views on children's mobile phone usage. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care, 12(12), 3351-3355.

Uzundağ, B. A., Koşkulu‐Sancar, S., & Küntay, A. C. (2024). Background TV and infant‐family interactions: Insights from home observations. Infancy, 29(4), 590-607.

Zelazo, P. D., & Carlson, S. M. (2012). Hot and cool executive function in childhood and adolescence: Development and plasticity. Child development perspectives, 6(4), 354-360.